Laser Counter-UAS and the Tier-1 Question: Opportunity or Premature Bet?

Laser counter-UAS is gaining traction in Europe, but scale remains unclear. Implications for Tier-1 suppliers.

From policy signal to industrial shift

“Today, the laser is the only means that guarantees precise targeting … It can’t be compared to anything else. We don’t see any alternatives today …” — Roman Knyazhenko, CEO, Skyeton

The Times recently reported that the UK is investing £20m in laser-based air-defence systems to counter drones. The amount is limited; the signal is not. Across Europe, laser air defence is increasingly discussed as an asymmetric response to mass drone threats – from Shahed-type attacks to persistent, unexplained drone activity around critical infrastructure.

For European Tier-1 suppliers, the relevance goes beyond defence budgets. Counter-UAS, particularly laser counter-UAS and directed-energy air defence, is beginning to resemble an industrial systems market, driven by scale, cost pressure, supply-chain reliability, and repeatability rather than bespoke, long-cycle weapons programs. These requirements closely match capabilities already present across Europe’s automotive and industrial supply base, particularly as parts of that ecosystem search for new growth vectors.

This raises a practical question for European suppliers: is laser air defence a market where Tier-1 defence suppliers and automotive Tier-1 suppliers can realistically create value, or does it remain a niche defined by primes, prototypes, and long timelines?

Where interest is coming from – but not yet scale

Across the UK, EU, and allied states, attention to laser counter-UAS is increasing. Governments face a structural problem: drone threats scale faster and cheaper than missile-based defences. Lasers are attractive not because they are decisive, but because they offer a different cost curve and can complement existing layers.

Elbit Systems, acting as the core laser module supplier to Rafael Advanced Defense Systems, transitioned Israel’s Iron Beam from development to serial production, with the first operational systems delivered to the IDF in late 2025 under contracts estimated at $500–800 million, and additional units already in production for nationwide deployment in 2026.

Parallel efforts in Israel, Russia, China and across NATO underline that laser counter-UAS is no longer exploratory competition, but a shared response to drone saturation, even if operational claims remain unproven.

Russia has announced plans for serial production of anti-drone laser systems following trials of eight platforms in June 2025, led by state corporations Rostec and Rosatom, though independent verification of deployment scale and operational effectiveness remains limited as of January 2026.

However, current investments remain exploratory rather than acquisitional. The UK’s £20m allocation, expanded EU defence funding channels, and parallel allied efforts all point to the same intent: de-risk architectures, mature subsystems, and test integration into layered air-defence networks. They do not yet define volumes, configurations, or timelines.

For Tier-1 suppliers, this distinction matters. Directional signals are strong; commercial visibility remains limited.

European primes are still de-risking laser technologies

This early stage is reinforced by the behaviour of Europe’s leading defence primes. In Germany, for example, MBDA and Rheinmetall are testing laser weapon demonstrators focused on beam bundling, source integration, beam stability, and real-time tracking. These trials are conducted in controlled environments and are aimed at validating foundational capabilities.

This is a critical signal. If primes are still proving how to combine and steer laser sources reliably, system architectures are not frozen and sourcing strategies remain fluid. From a Tier-1 perspective, the market is still forming upstream of procurement.

Ukraine as the operational stress test for laser air defense

Ukraine provides the clearest view of how laser systems behave under real conditions. Prototypes have demonstrated that lasers can disable drones within narrow operational windows. At the same time, Ukraine shows why scale remains elusive.

Weather sensitivity, power availability, cooling limits, and tracking accuracy constrain effectiveness. The challenge is not generating laser power, but holding a precise beam on a fast-moving target for several seconds, repeatedly and reliably.

Fulltime Robotics’ SlimBeam product has progressed from a lab-stage high‑power (1.5 kW) laser turret concept to a field-tested, government‑supported prototype capable of neutralizing small drones at up to roughly 800 m and blinding UAV optics out to about 2 km, with ongoing work on automated tracking and portable rifle‑style variants as of mid‑2025, with no recent news available.

Ukraine’s experience shows that the remaining bottlenecks are not laser physics, but automation, integration, and reliability at scale, precisely where industrial suppliers add leverage.

Tryzub (Trident) laser weapon system progressed from initial testing and operational deployment announcements in December 2024 through demonstrated field capabilities in early 2025, with reported ranges of 2-5 km against aerial targets including drones and aircraft, though operational details remain limited and independent verification is lacking as of January 2026.

Ukraine should therefore be read as a stress test, not a verdict.

What laser counter-UAS means for Tier-1 suppliers

Taken together, the picture is consistent. Laser counter-UAS is no longer speculative, but it is not yet a scale market. Outside of Israel’s uniquely centralised Iron Beam program, no country has committed to large-volume procurement.

Israel’s Iron Beam remains the only example of a multi-year, hundred-million-dollar commitment, highlighting that under the conditions scale is possible – but only under tightly defined point-defence and procurement conditions.

In the current phase, Tier-1 suppliers benefit most from:

- subsystem pilots and qualification,

- dual-use adaptation of existing products,

- early technical alignment with primes,

- influence over architectures and standards.

It does not yet justify capacity investment, defence-only product lines, or volume-driven strategies.

Where Tier-1 capabilities map to prime weaknesses

In current laser counter-UAS programs, defence primes retain strength in system integration, sensors-of-record, and programme management. Their weakest points sit elsewhere, specifically in subsystems that must combine industrial robustness, cost discipline, and repeatability. This is where Tier-1 suppliers create disproportionate value.

Power electronics

Primes struggle with high-density, efficient power conversion and buffering outside bespoke designs. Laser systems are often duty-cycle-limited not by laser physics, but by power stability, transient handling, and component lifetime. Automotive-grade power electronics suppliers outperform primes in efficiency optimisation, thermal derating, and cost scaling.

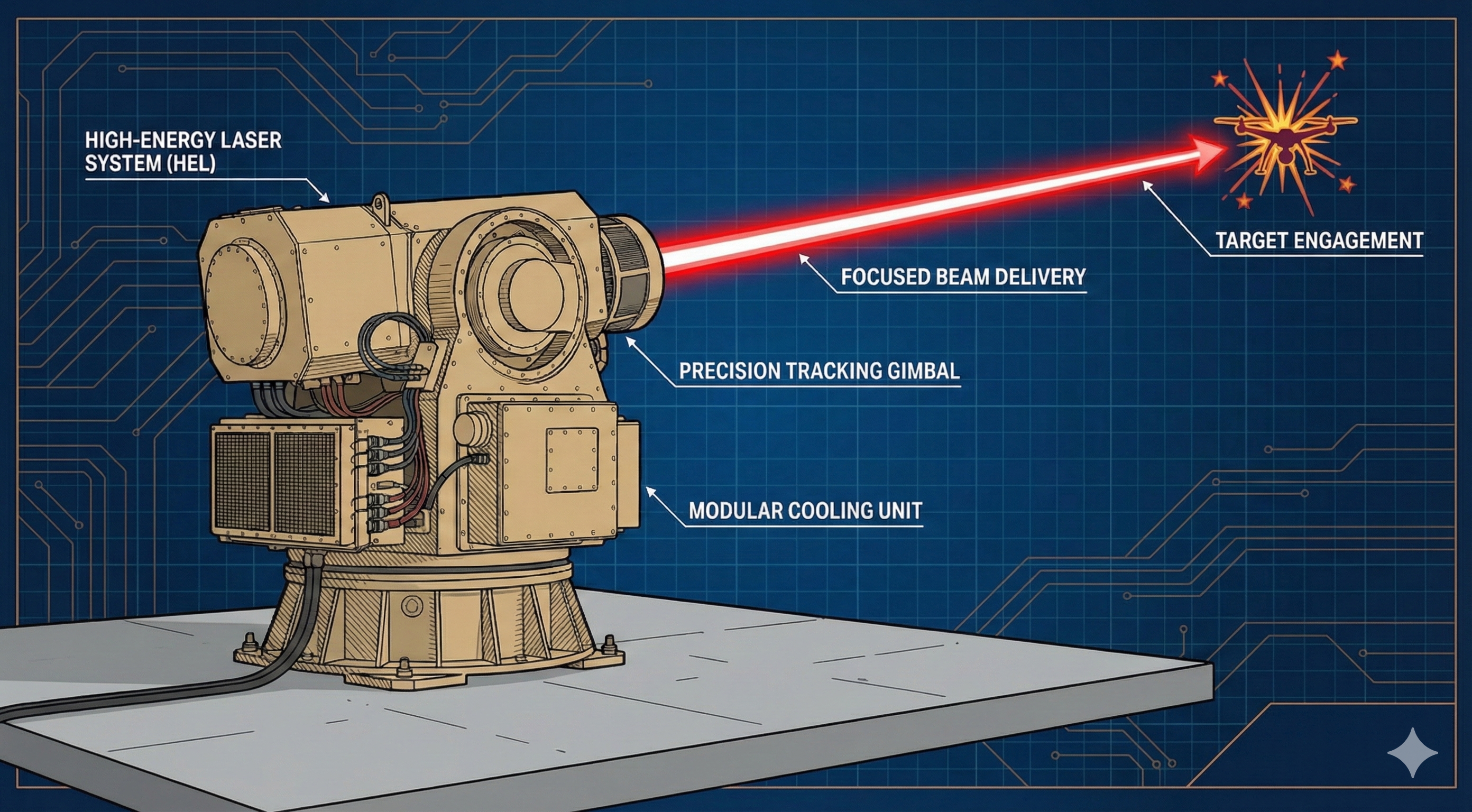

Thermal management

Cooling remains one of the dominant constraints on sustained laser operation. Primes typically rely on conservative, oversized solutions that limit uptime and mobility. Tier-1 suppliers bring mature liquid-cooling architectures, compact heat exchangers, and lifecycle-tested components that directly increase duty cycle and system availability.

Motion control and stabilisation

Holding a laser on a fast-moving target for several seconds is a precision control problem. Primes are strong in pointing mechanisms but weaker in high-volume, vibration-tolerant actuators and drives. Automotive and industrial Tier-1s excel in stabilisation, servo control, and reliability under continuous operation.

Sensors and tracking

While primes integrate EO/IR sensors, they often lag in real-time fusion, prediction, and tracking robustness against clutter and rapid manoeuvres. Tier-1s with ADAS and industrial vision heritage bring mature algorithms, hardware acceleration, and validated perception stacks that improve hit probability more than marginal laser power increases.

Real-time computing and control

Many laser demonstrators still rely on semi-manual or loosely automated control loops. Deterministic, safety-critical real-time systems are not a prime strength. Tier-1 suppliers with automotive ECU and industrial automation experience can close control loops, reduce operator burden, and enable scalable deployment.

Why this matters commercially

These weak points are not peripheral. They determine:

- system uptime,

- engagement probability,

- maintenance burden,

- and cost per defended asset.

As laser counter-UAS moves from demonstration to deployment, value shifts away from the laser itself toward the subsystems that make it usable at scale. This is precisely where Tier-1 suppliers are strongest, and where primes are most dependent.

Final takeaway

Laser-based counter-UAS has become a shared strategic direction across Europe and its partners, driven by drone saturation and unsustainable interceptor economics. At the same time, current programs, from UK funding to European prime demonstrators and Ukraine’s battlefield experience, show that the technology has not yet crossed into an industrial procurement phase.

What exists today is a market-shaping window. Governments are de-risking, primes are validating, and operational use is exposing the remaining gaps. The constraints are no longer about feasibility, but about automation, integration, power and thermal management, and repeatable manufacturing.

For European Tier-1 suppliers, the question is not whether the market is ready, but whether to engage while it is still being defined. Those who position early can shape future systems and economics; those who wait for certainty may find the critical decisions already taken.